Almost all of Africa’s ancient artistic heritage and natural history collections are preserved in European countries: the United Kingdom, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Vienna, and Belgium. Difficult as it may be to articulate the magnitude of this reality, it is even more difficult to learn how such previous cultural identities were looted and stolen from their birthplace.

The restitution of African Art has long been a conversation since the year of Africa, 1960 when the independence movement began. In addition to African art, Africa’s natural history collections contain countless botanical, geological, and human specimens— prestigious unique specimens that were also extracted from Africa. For example, the fossil bones of the largest dinosaur known to the world, a one hundred and fifty million years old fossil that was extracted from Tanzania now displayed in Berlin, Germany since the 1930s.

For centuries, Africans have been described as people without history, culture, or civilization and that Africans never invented anything therefore, Africans are without any past or history. Yet, African inventions and natural history lay on full display in the institutions and homes of the very people who claim Africans are without any history. The audacity, bold hypocrisy, and blatant blindness are the deliberate attempts to make African history and any contributions by Africans to our world oblivious.

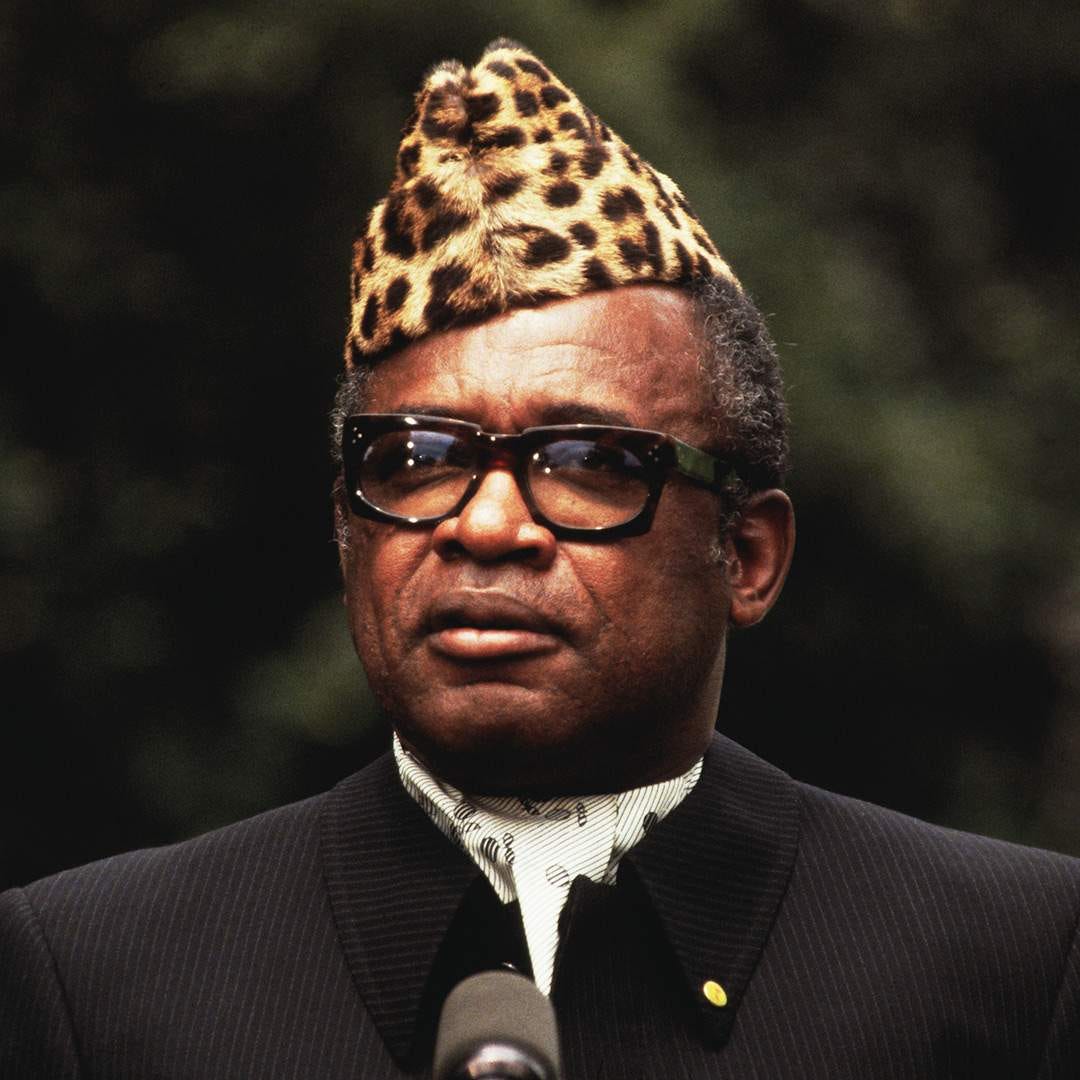

I am in no way an artist nor an art historian however, I am passionate about cultural preservation and an inveterate passion for culture, traditions, history, storytelling, etc. In “Africa’s Struggle for Its Art,” the author Bénédicte Savoy brings to light this largely unknown but deeply important history. One of the world’s foremost experts on restitution and cultural heritage, Savoy investigates extensive, previously unpublished sources to reveal that the roots of the struggle extend much further back than prominent recent debates indicate, and that these efforts were covered up by myriad opponents. Savoy looks at pivotal events, including the watershed speech delivered at the UN General Assembly by Zaire’s president, Mobutu Sese Seko, which started the debate regarding the restitution of colonial-era assets and resulted in the first UN resolution on the subject. She examines how German museums tried to withhold information about their inventory and how the British Parliament failed to pass a proposed amendment to the British Museum Act, which protected the country’s collections.

Moreover, Savoy highlighted a pivotal film by a Ghanaian film director Niki Kwate Owoo, which premiered at London’s Africa Center on January 20th, 1971 titled, “You Hide Me.” The film not only attracted interests far and wide but also shared some light on how museums have looted precious cultural objects whose spirits are kept in boxes, behind cold and clinical glass barriers — objects that are religious, spiritual, and sacred in display at museums and for people who have no spiritual connections to them nor understand their spiritual meaning better yet, how they even got there.

Central to the film’s theme is the restitution of African cultural property. The first half of the film showcases the work of three African artists who are active representatives of the London pan-African Art scene. It was the second half of the film that delved deeper into the title of the film. The camera followed a young black man and a woman (Owoo and Margaret Prah) through the basement vault of the British Museum where they unwrap African objects hidden away in boxes and plastic bags among them were wooden statues, jewelry, a sword, a stool, and various African marks. The film was shot in a day within eight hours as those were the conditions granted to Owoo and his crew. “We came across an enormous collection…. Thousands of important works of art that had never been exhibited.

The film also highlighted the realities of the 1987 destruction and looting of Oba’s palace in the city of Benin by the British colonial expedition in February 1897. Among other goods, the British plundered over 900 bronze sculptures of exquisite aesthetic quality and technical mastery. “The commentator describes the violent provenance of the objects using terms such as “loot” and “sack” (about Benin City, modern-day Nigeria). He speaks of their invisible “captivity in boxes and plastic bags” and condemns the systematic, “tactically” intended destruction of cultural, religious and artistic traditions in Africa by colonial administrations. Even more important is the realities of the hierarchization of cultures by ethnological museums while underling the ideological instrumentalization of African collections in Europe and the United States: “The material they collected in Africa was used as propaganda material against Africa and people of African descent.”

After centuries of power, a single event marks a stark turning point in the history of the Benin kingdom. James Phillips, an official in Britain’s Niger Coast Protectorate, led an unarmed trading expedition to Benin City in January 1897. To prevent the British party from interfering with annual royal rituals, some chiefs, acting against Oba Ovonramwen’s wishes, ordered the expedition attacked. Six British officials and almost 200 African porters were killed.

Britain responded immediately, mounting a so-called punitive expedition to capture Benin. The palace was burned and looted in February 1897, and the oba was exiled. To break the power of the monarchy, the British confiscated all of the royal treasures, giving some to individual officers but taking most to auction in London to pay for the cost of the expedition. The looted objects eventually made their way into museum and private collections around the world. The objects remain contested today, with some Nigerian scholars and museum professionals and the royal court of Benin advocating for their return.

According to court historians and the accounts of early 17th-century Dutch travelers, the oba (king) of Benin once covered the posts of his palace courtyard with hundreds of copper alloy plaques, such as those on view..

Plaques are individually molded and cast with molten copper-based metal. While some plaques have narrative scenes, such as battles and hunts, most—like these examples—have one, two, or more male figures in royal attire carrying court regalia, such as swords, bows, and gongs. Close inspection of the plaques reveals a high level of technical expertise and a wealth of historical detail that provides a glimpse into Benin court life centuries ago.