In celebration of Juneteenth, a day that is also commemorated as a second independence day we want to highlight a little-known book that served as a travel guide for so many.

On June 19, 1865, nearly two years after President Abraham Lincoln emancipated enslaved Africans in America, Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas to ensure that all enslaved people be freed. More than 250,000 African Americans embraced freedom by executive decree in what became known as Juneteenth or Freedom Day. Juneteenth honors the end of slavery in the United States and is considered the longest-running African American holiday. On June 17, 2021, it officially became a federal holiday. Although it has long been celebrated in the African American community, this monumental event remains largely unknown to most Americans. The Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, established that all enslaved people in Confederate states in rebellion against the Union “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

I shall never forget that memorable night when in a distant city waited and watched at a public meeting, with 3,000 others not less anxious than myself, for the word of deliverance which we have heard read today. or shall ever forget the outburst of joy and thanksgiving that rent the air when the lightning brought to us the emancipation proclamation. — Fredrick Douglas

Although all enslaved people were free, however, “the rhetoric of the American Revolution, with its invocation of inalienable rights and universal freedom, had led to heated debate over the access of African Americans to these rights,” Library of Congress. Among the rights which may be reckoned is the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties. These rights became a civil rights issue and one of them was the right to travel. Segregation meant that facilities for African American motorists in some areas were limited, but entrepreneurs of varied races realized that opportunities existed in marketing goods and services specifically to black patrons. These included directories of hotels, camps, roadhouses, and restaurants that would serve African Americans.

During the Jim Crow era when open and often legally prescribed discrimination against African Americans especially and other non-whites was widespread, many black Americans took to driving, in part to avoid segregation on public transportation. As the writer George Schuyler put it in 1930, “All Negroes who can do so purchase an automobile as soon as possible in order to be free of discomfort, discrimination, segregation, and insult.” Black Americans employed as athletes, entertainers, and salesmen also traveled frequently for work purposes using automobiles that they owned personally. However, many motorists faced a variety of dangers and inconveniences along the road, from the refusal of food and lodging to arbitrary arrest.

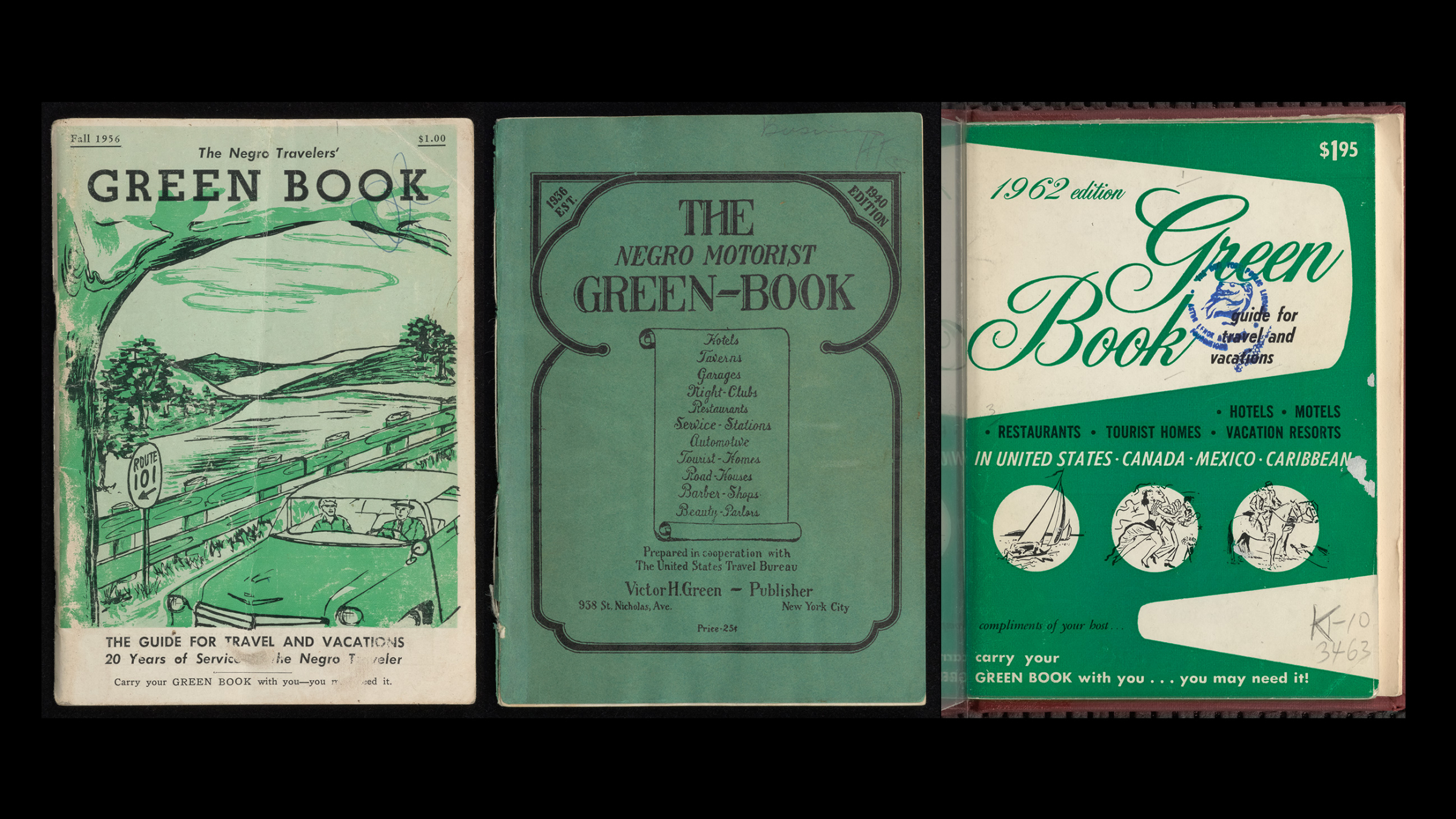

Consequently, The Negro Motorist Green Book was put into publication. It’s an inspiring story of how we — if we have the capacity make life better and accessible for each other. At a time when African Americans were denied the basic rights to move freely and travel and were being treated in an undignified manner being refused to stay at a motel or hotel, denied service at a restaurant having to seat at the back of a railroad cart, or a bus, Victor Hugo Green, a World War I veteran from New York City who worked as a mail carrier and later as a travel agent created The Negro Motorist Green Book.

From a New York-focused first edition published in 1936, Green expanded the work to cover much of North America, including most of the United States and parts of Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, and Bermuda. The Green Book became “the bible of black travel during Jim Crow”, enabling black travelers to find lodgings, businesses, and gas stations that would serve them along the road. It was little known outside the African American community. Shortly after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed the types of racial discrimination that had made the Green Book necessary, publication ceased and it fell into obscurity. There has been a revived interest in it in the early 21st century in connection with studies of black travel during the Jim Crow era.

Its principal goal was to provide accurate information on black-friendly accommodations to answer the constant question that faced black drivers: “Where will you spend the night?” The guide also helped recirculate the money spent by tourists within the black community.

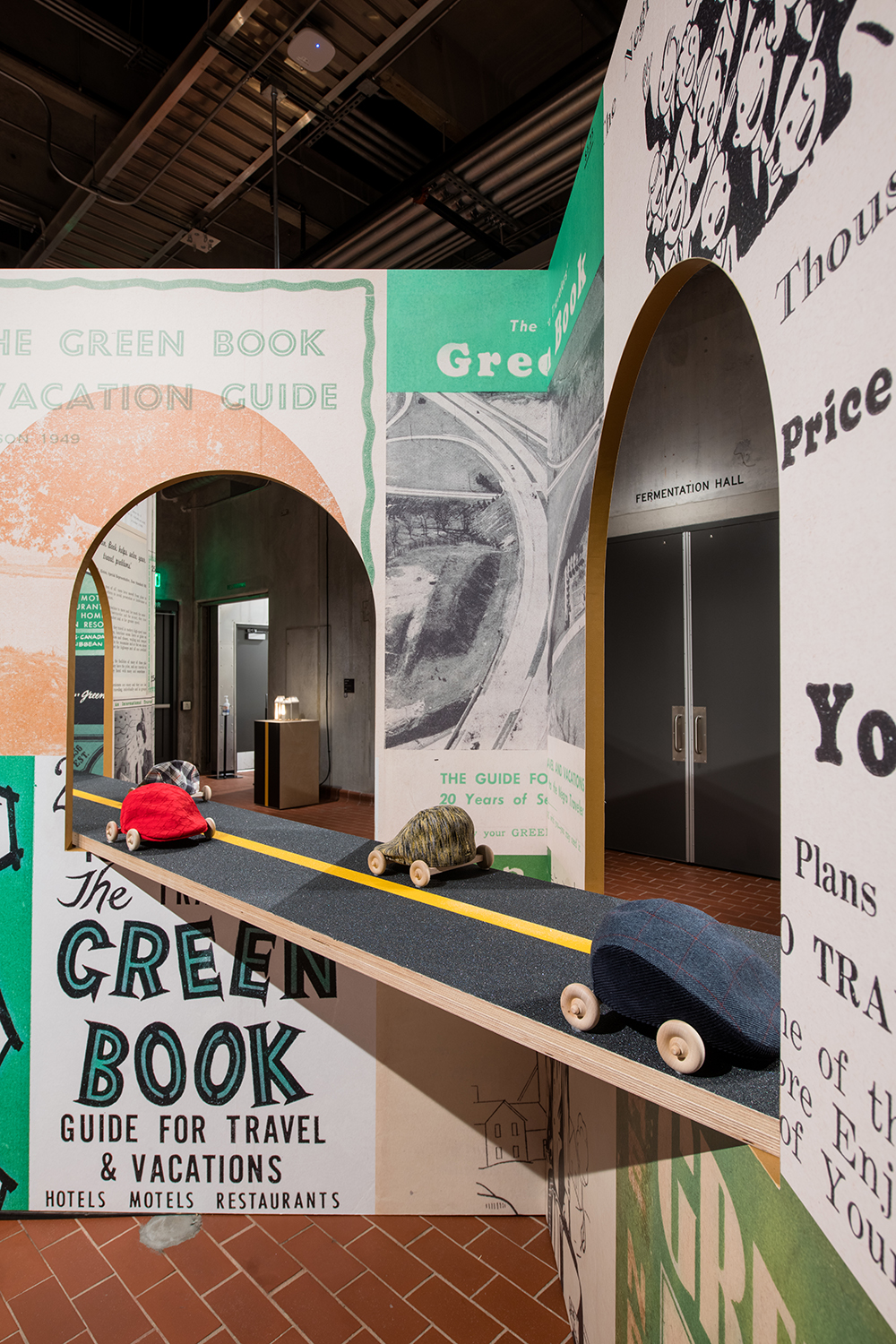

Art Work: by Derrick Adams, Sanctuary consists of 50 works of mixed-media collage, assemblage on wood panels, and sculpture presented in an installation designed by the artist that reimagines safe destinations for the black American traveler during the mid-twentieth century. The body of work was inspired by The Negro Motorist Green Book.