Within the loop of the Niger River in Mali, between the town of Mopti and the Burkina Faso border, there is a place where steep cliffs at the edge of an arid plateau dominate a sandy plain. Over 500 meters high in places, the escarpment is fissured with deep ravines, where rain caught in the cracks of the grey rock supports the growth of dense and varied vegetation. This is the Land of the Dogon.

The Dogon, who today number about 300,000, are of the Malinke (Mandingo) ethnic group. Their ancestors are thought to have fled from the Mali Empire under the reign of Sundiata Keita in the fifteenth century and found refuge at the Bandiagara cliffs, where they displaced another people, the Tellern, who left behind abundant evidence of their own cultural traditions in tombs set in caves in the rock face.

The communities at the site are essentially the Dogon and have a very close relationship with the environment expressed in their sacred rituals and traditions. The Land of the Dogon is the outstanding manifestation of a system of thinking linked to traditional religion that has integrated harmoniously with architectural heritage, very remarkably in a natural landscape of rocky scree and impressive geological features. The relationship of the Dogon people with their environment is also expressed in the sacred rituals associating spiritually the pale fox, the jackal, and the crocodile.

Animals such as the fox, snake, and the crocodile are sacred animals that have a place in Dogon mythology and may never be killed. The Baobab tree is also a sacred tree which can never be cut or sold. The Pale Fox was an unnatural and socially disruptive creature born out of the first mating of Amma and Mother Earth. Amma was the main god of the Dogon. He created the sun, the earth, and the people. After Amma created Mother Earth out of clay, he raped her and she gave birth to several sets of twins, which form a pantheon of Dogon mythical beings. All divine children were born as twins with a male and female counterpart; however, the pale fox was born without placenta and did not have a female twin. That is why he is a symbol of loneliness. The myth of the pale fox is about the chaos that resulted from an imbalance of male and female qualities, and it is the bringer of anarchy.

According to Dogon cosmogony, from the union of the supreme deity Amma and his creation, the Earth, issued a being known as the Pale Fox. Unique and imperfect, the Fox introduced the principle of disorder into creation. It is associated with human weakness and the anarchy inherent in the universe. Amma also created Nommo, a hermaphroditic creature who represents celestial harmony and is linked symbolically to water and to fecundity. The Nommo are fish-like creatures with a human torso and the tail of a snake. They are the mythical twins born out of the second mating of Amma and Earth and water spirits. Then Amma modelled a human couple from clay. They gave birth to the eight ancestors of the Dogon, whom Nommo taught to speak.

Every aspect of Dogon domestic, social, and economic life is linked to this cosmogony. Villages are designed in the image of the cosmos. Built on rock to preserve scarce arable land, they are laid out on a north-south axis in the form of a prone human body, supposedly that of Nommo, the great ancestor. The head is represented by the togu net (literally, “big shelter”), a meeting-place reserved for men. This open-sided structure is always the first to be built in a new village. It consists of a platform on which stand several rows of rough-hewn timber pillars that support a roof of branches topped by a thick mat of millet straw. The number of pillars has symbolic significance. Decisions taken in the togu na are solemn and irrevocable.

The social and cultural traditions of the Dogon are among the best preserved of sub-Saharan Africa, despite certain important irreversible socio-economic mutations. The villages and their inhabitants are faithful to the ancestral values linked to an original lifestyle. The harmonious integration of cultural elements (architecture) in the natural landscape remains authentic, outstanding, and unique. Nevertheless, the traditional practices associated to the living quarters and the building constructions have become vulnerable, and in places the relationship between the material attributes and the outstanding universal value are fragile.

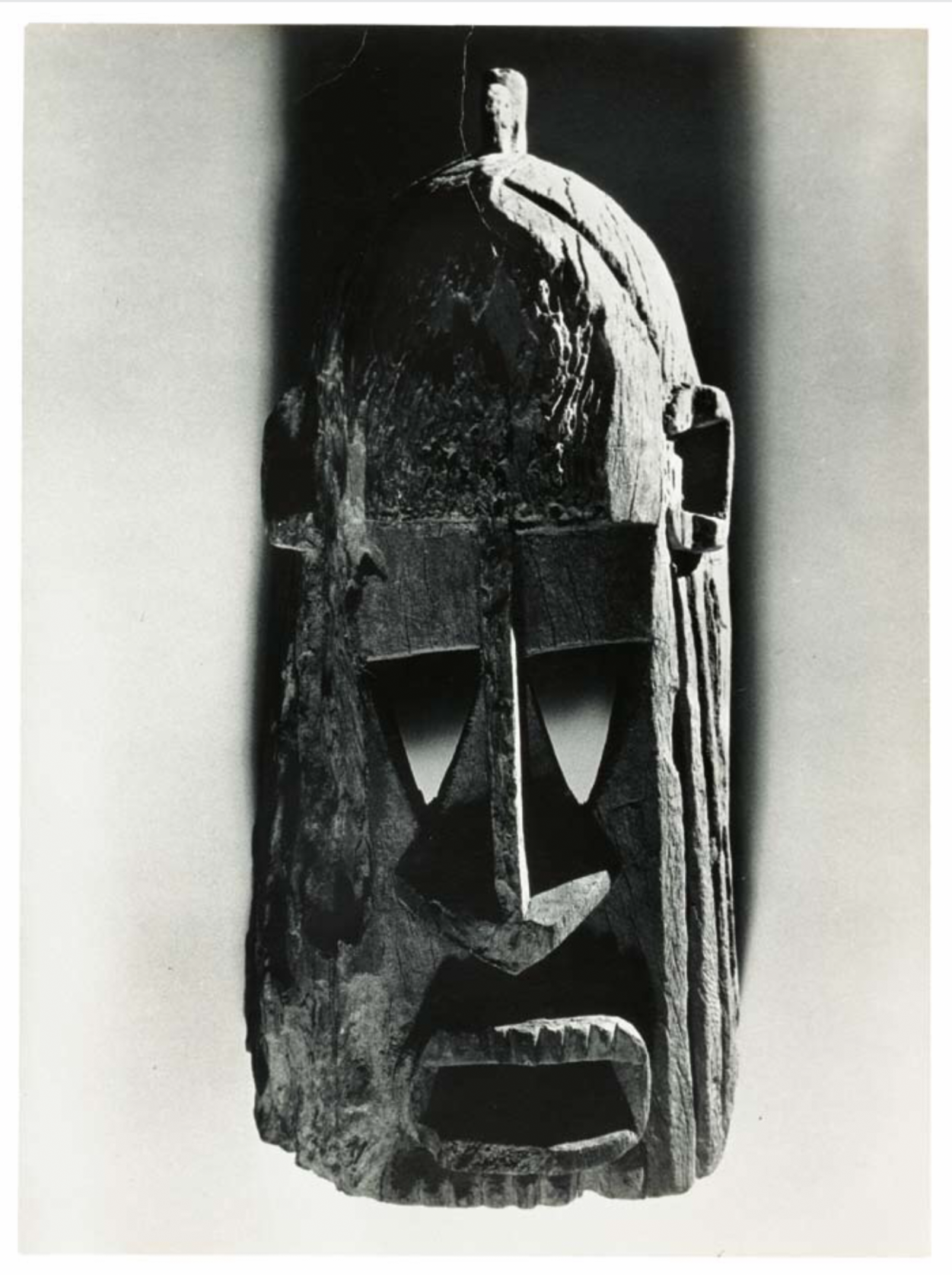

Ritual is embedded in Dogon life and carved or constructed objects are an integral part of this, including, most famously, the masks used at funerary or remembrance ceremonies. But these are not just objects. In the words of one anthropologist who has worked in Dogon society: “The term mask usually suggests a face or head covering that disguises the natural head…For the Dogon, however, the èmna consists of a person dancing in a costume that includes a headpiece but is not limited to it. According to Emmanuel Sougez, Untitled (Dogon hermaphrodite rider), reproduced in Marcel Griaule, Art de l’Afrique Noire, 1947 quoting from a ritual Dogon verse: “The eye of the mask is an eye of the sun / The eye of the mask is an eye of fire.” Masks are not worn; masks are men who dance, perform, and shout.” Once the physical headpieces have been used in the ritual dance, they have no further purpose. Consequently, they are discarded and left to rot. Many negrophilist who have visited and studied the Dogon have dug some of the buried masks that we see in many western museums today. An essay by Ian Walker, VI. Out of Phantom Africa: Michel Leiris, Man Ray and the Dogon described how two anthropologist dug hermaphrodite figure which I find disturbing as these are ancestral objects that are a part of the Dogon people’s culture and may as well be sacred. “The most remarkable single object that they collected was a hermaphrodite figure, about fifty-two inches high and curved in the shape of the tree from which it was carved. It was discovered buried in the ground. “The head, which was all that was visible, was being used as a post for hitching horses.” The locals would not help to dig it up, saying “these things were already there when our ancestors arrived,” so Paulme and Lifchitz dug it out with their pocketknives.”

No tribe has fascinated ethnologist, anthropologist, astronomers, negrophilist and the like than the Dogon tribe. The Dogon has confounded western astronomers with their knowledge of the Sirius Star. They revealed to French astronomers their knowledge that Sirius is made up of three stars, and that one of them revolves around the other in a cycle of sixty years. While the westerners say they have not found the third star, they say it is impossible that the Dogon could have acquired this information without external assistance and support because the star is too far to see with the naked eye. Most importantly, the Dogon knew about Sirius B and its orbit around Sirius A thousands of years before western astronomers found out about it. According to the Dogon their knowledge of this fact was from visitors from Sirius, who arrived in a vessel that made a lot of noise. Watch the 1969 version of the event by the French ROUCH Jocelyne . The version is in French and there is no English translation available.

Sigui 1969 – The Cave of Bongo

Moreover, the Dogon celebrates Sigui mask festival around every 60 years. It’s an event determined by the position of Sirius in the night sky. It takes many years for it to be completed. The last Sigui took place from 1967 to 1973, the next one will begin in 2032. We will be there to witness such magnificent festival with our groups and fellow inveterate culturally curious explorers.

Feeling Inspired?: Visit our African Homecoming page — a page dedicated to African history, Africa’s great civilizations, people, places, history, culture, and traditions and uncover the untold stories of the diverse and vast African continent. Encompassing a wide range of experiences, the page is inspired by our travelers who are cultural ambassadors, erudite for ebullient discussions, gluttons for authentic cultural experiences and stories, with an inveterate passion for travel. We’re always here to take the guesswork out of your travel experiences to the African continent – experiences that shift perspectives and fuel imagination.