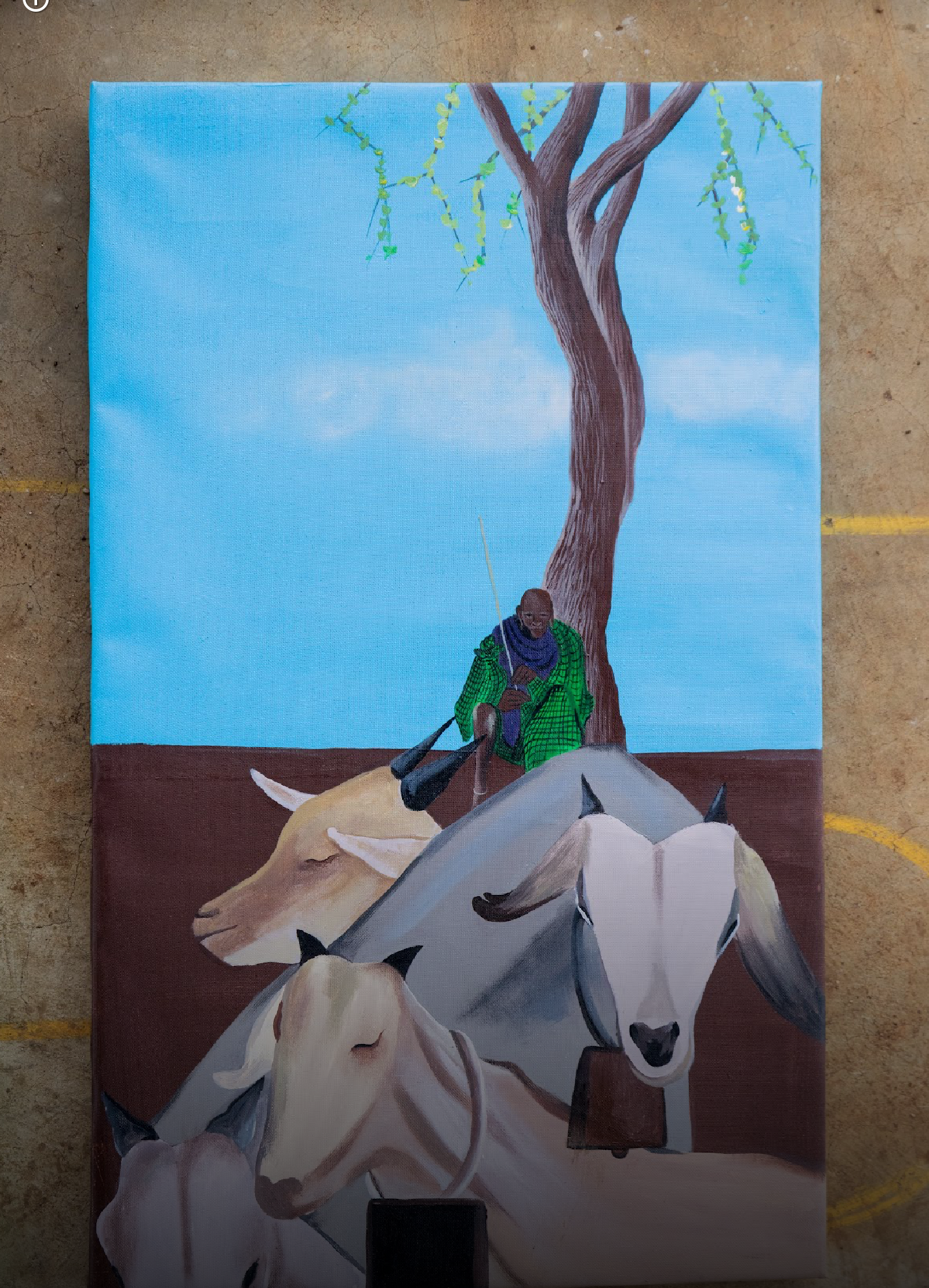

A highlight for many safari travelers in East Africa is visiting and meeting with the Maasai people. The Maasai are a semi-nomadic, pastoral indigenous tribe whose ancestral territory stretches across southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, and they live by herding cattle and goats. Kenya recognizes over fifty tribes of native people. The Maasai were the dominating tribe at beginning of 20th century. In addition, the Maasai are one of the oldest communities in the world and viewed as Africa’s last great warrior tribe that has thrived in the great rift valley region of East Africa for over 2000 years. They are revered for their cultural traditions, lifestyle and lore and how well preserved tradition in the face of modernity. Since the Maasai live in proximity with the wildlife, it is as though the two co-exist as many Massai communities abut within the bounds of popular game preserves—including Maasai Mara, Ngorongoro and Amboseli.

The Maasai community traditionally believed in God (referred to as Enkai), and that God created the earth with three groups of people. It is said that the Maasai originated to earth by sliding down from a rope linked to heaven. They believe the sky god Eng’ai, who lowered them to earth on a leather thong gave the cattle to them. Eng’ai is neither male nor female but seems to have several different aspects. The Maasai believe Eng’ai is the creator of everything. Cattle are cherished and is their source of income and nourishment, with the Maasai diet supplemented by a mixture of cow milk and blood. Other known legends and folklore tales include the story of Olenana, who deceived his father to obtain the blessing reserved for his older brother Senteu.

The Maasai have a very patriarchal society in which Masai men and elders make all the important decisions for the tribe. Spiritual leaders, known as Oloiboni or Loibon, were common in each Maasai family. Oloiboni had mystical as well as medicinal healing powers. They predicted the future and healed people from physical, mental, and spiritual illnesses. They oversee the rituals, led the community in sacrifices, officiated ceremonies, and advised elders on spiritual aspects. They were also prophets, shamans, and seers. Pictured here is a horn with a leather lid. It was used by Loibon to store medicine.

The tribe measure a man’s wealth in terms of the number of children they have and heads of cattle. The more the better. The hides are used to make furniture and the bones are used to create tools. The Maasai are easily recognized by their tall, slender build wrapped in red patterned swatches of cloth known as ‘Shúkà’ cloth, along with their long, large blade spears. The shuka bears a history as rich as its colours. Often red with black stripes, shukacloth is affectionately known as the “African blanket.” Wearing the Shuka enforces the Maasai cultural heritage as a warrior tribe, and Shuka cloth plays a prominent role in their clearly defined life milestones. It’s known to be durable, strong, and thick — protecting the Maasai from the harsh weather and terrain of the savannah. The origin of Shuka is not very clear, however, there are a few schools of thought. Prior to colonialization, the Maasai wore leather garments but only began to replace calf hides and sheep skin with commercial cotton cloth in the 1960s. One of the schools of thought is traced back the origin of shuka through centuries — fabrics were used as a means of payment during the slave trade and landed in East Africa, while black, blue, and red natural dyes were obtained from Madagascar. There were records of red-and-blue checked “guinea cloth” becoming very popular in West Africa during the 18th century. Another interesting explanation is that the Maasai cloth was brought in by Scottish missionaries during the colonial era. The Africa Inland Mission was established in 1895, and until 1909 Kenya was its only operation. This may sound like a logical explanation — however, the story cannot be validated for sure. Although, shuka cloth does resemble the Scottish plaid or tartan patterns so the story could be verse versa. Today, shuka cloth is largely manufactured in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and even in China, bearing text such as “The Original Maasai Shuka” on the plastic packaging.

The Maasai are well known for their jumping dance. Among the many singing and dancing ceremonies practiced by the tribe, the best-known is the adamu Moran dance. In this ritual, young Maasai men gather in a semicircle while rhythmically chanting in unison; then, each takes a turn stepping in front of the group, and jumping several times straight up in the air, as high as he can. Their stance is narrow, and they ensure that their heels don’t touch the ground. This dance is a big part of the Maasai celebrations and rituals, especially during the coming-of-age ceremony, as it is traditionally regarded as a mating dance. Through this dance, the new Morans display their strength in a bid to impress the women. The women respond by joining the dance and singing in their own rhythm. They indicate through their movements if they are interested in the Morans. Other than this ceremony, the community also celebrates other rituals by dancing, like marriage or the selection of a village chief. African safari travelers are often thrilled by the display, and some even attempt the jumping dance themselves. Very few can approach the heights reached by the warriors, though; they have been practicing since childhood. The Maasai have a very colorful culture of music and dance. The women are known to recite lullabies, hum and sing songs of praise about their sons. There’s always one song leader, known as an olaranyani, who leads the group in song.

As part of the Maasai coming of age ceremony young Maasai warriors call Morans from a very young age, are trained to become warriors by taking on responsibilities, learn to respect elders and acknowledging the tribe by hunting down a lion. This ritual was always an integral part of being recognized as a true Maasai warrior; however, the decline in lion population raised concerns among conservationists, who figuratively managed to pull a rabbit out of a hat to save the East African lions. Since the tribe inhabits a sizeable geographical region covering southern Kenya and the northern part of Tanzania, this coincidentally eclipses several game conservation areas. As the tribe’s population grows this encroach on game conservation territories due to expanded grazing lands for their cattle.

In an article by the Daily Beast, “The Kenyan Maasai Who Once Hunted Lions Are Now Their Saviors” between the year 2000 and 2011, more than two hundred lions were hunted and killed by Maasai warriors, equivalent to 40% of the lion population each year. The lion population in Africa recorded in 2013 stood at fewer than 30,000 compared to half a million in 1950. These staggering statistics led scientists to predict that the lion would be extinct in Kenya by 2020. These hunts, combined with habitat loss, poaching, and disease, caused the lion population across Africa to plummet from half a million in 1950 to fewer than 30,000 in 2013. A decade ago, scientists worried the lion could be extinct in Kenya by 2020. However, today the area’s lion population is thriving thanks to an extraordinary group. In the Maasai-owned lands of southern Kenya and northern Tanzania known as Maasailand, the lion population has rebounded. “We’re now having conversations around what to do with so many lions,” said Egyptian American conservationist Dr. Leela Hazzah.

Dr. Hazzah is the co-founder of Lion Guardians, a nonprofit that gives Maasai warriors who once killed lions the responsibility for protecting them. Building on their traditional tracking skills, the warriors learn to fit lions with tracking collars, then use radio telemetry antennas and GPS receivers to follow their movements and warn villagers and herders if a lion is in the vicinity to thwart any conflict. Lions form part of the attraction to East African tourism. Without this turnaround to protect the lions, there may have been dire consequences for tourism which the Maasai capitalize upon.

There is a popular Maasai proverb that goes- “The bell rings to tell the cow she can continue to eat but there is no bell to tell you when to stop.” The proverb, shared by Lobodlo, could come to mean that there is no external reminder or stop signal for us to know when to end certain actions, and we must rely on self-discipline and control to regulate our behavior.

Getting There: Visit our African Homecoming page — a page dedicated to African history, Africa’s great civilizations, people, places, history, culture, and traditions and uncover the untold stories of the diverse and vast African continent. Encompassing a wide range of experiences, the page is inspired by our travelers who are cultural ambassadors, erudite for ebullient discussions, gluttons for authentic cultural experiences and stories, with an inveterate passion for travel. We’re always here to take the guesswork out of your travel experiences to the African continent – experiences that shift perspectives and fuel imagination.