The Ashanti (or Asante) are the dominant ethnic group of a powerful 19th-century empire and today one of Ghana’s leading ethnic groups, with more than two million members concentrated in south-central Ghana. The Ashanti Empire was a pre-colonial West African state that emerged in the 17th century in what is now Ghana. The Ashanti are an ethnic subgroup of the Akan-speaking people, and the last group to emerge out of the various Akan civilizations, composed of small chiefdoms. Twi, dialect of the Akan language spoken in southern and central Ghana by several million people, mainly of the Akan people, the largest of the seventeen major ethnic groups in Ghana. Twi has about 17–18 million speakers in total, including second-language speakers; about 80% of the Ghanaian population speaks Twi as a first or second language and it is spoken by over nine million Asante people also as a first or second language. Twi has a simple tonal language system which is reflected in its phonology.

The Asante people developed the Ashanti Empire, along the Lake Volta and Gulf of Guinea. The empire was founded in 1670, and the capital Kumasi was founded in 1680 by AsanteheneOsei Kofi Tutu I on the advice of his premier priest Okomfo Anokye. Anokye unified the independent chiefdoms into the most powerful political and military state in the coastal region. The Asantehene organized the Asante union, an alliance of Akan-speaking people who were now loyal to his central authority. The Asantehene made Kumasi the capital of the new empire. Sited at the crossroads of the Trans-Saharan trade, Kumasi’s strategic location contributed significantly to its growth. Anokye also created a constitution, reorganized, and centralized the military, and created a new cultural festival, Odwira, which symbolized the new union. Most importantly, he created the Golden Stool, which he argued represented the ancestors of all the Ashanti. Upon that Stool Osei Tutu legitimized his rule and that of the royal dynasty that followed him.

The Golden Stool is a sacred symbol of the Ashanti nation believed to possess the sunsum(soul) of the Ashanti people. According to legend, the Golden Stool — sika ‘dwa in the Akan language of the Ashanti — descended from heaven in a cloud of white dust and landed in the lap of the first Ashanti king, Osei Tutu, in the late 1600s. The king’s priest, Okomfo Anokye, proclaimed that henceforth the strength and unity of the Ashanti people depended upon the safety of the Golden Stool. Drawing upon the Akan tradition of a stool indicating clan leadership, the Golden Stool became the symbol of the united Asante people and legitimized the rule of its possessor. To defend the stool in 1900, the Ashanti battled the British in the Yaa Asantewa War. The Ashanti chose to let the British exile the Ashanti’s last sovereign king, Prempeh I, rather than surrender the stool. Today the Golden Stool is housed in the Asante royal palace in Kumasi, Ghana.

From 1698 to 1701, the united Ashanti army defeated the Denkyira people, who had conquered the Ashanti in the early 17th century. Over the course of the 18th century, the Ashanti conquered most of the surrounding peoples, including the Dagomba. By the early 19th century, Ashanti territory covered nearly all of present-day Ghana, including the coast, where the Ashanti could trade directly with the British. In exchange for guns and other European goods, the Ashanti sold gold and slaves, usually either captured in war or accepted as tribute from conquered peoples. Gold was the major product of the Ashanti Empire. Osei Tutu made the gold mines royal possessions. He also made gold dust the circulating currency in the empire. Gold dust was frequently accumulated by Asante citizens, particularly by the evolving wealthy merchant class. However even relatively poor subjects used gold dust as ornamentation on their clothing and other possessions. Larger gold ornaments owned by the royal family and the wealthy were far more valuable. Periodically they were melted down and fashioned into new patterns of display in jewelry and statuary.

Although, the early Ashanti Empire’s economy depended on the gold trade in the 1700s, however, by the early 1800s it had become a major exporter of enslaved people. The slave trade was originally focused north with captives going to Mande and Hausa traders who exchanged them for goods from North Africa and indirectly from Europe. By 1800, the trade had shifted to the south as the Ashanti sought to meet the growing demand of the British, Dutch, and French for captives. In exchange, the Ashanti received luxury items and some manufactured goods including most importantly firearms.

As they prospered, Ashanti culture flourished. They became famous for gold and brass craftsmanship, wood carving, furniture, and brightly colored woven cloth, called kente. Much more than just an ordinary fabric, kente cloth has been worn by Ashanti kings, queens, and important figures of state in Ghana since the 12th century and has evolved into the prime representative of many principals of African culture. Now made from cotton or silk, the first cloth was woven from raffia fibers, and the designs were so like basket weaving patterns that the cloth was given the name “kente,” a derivative of “kenten,” the Ashanti word for basket. Today, over 300 different types of kente cloth are recognized, and the fabric is available in a variety of colors, sizes, and designs, all of which symbolize numerous aspects of social and cultural life. Women tend to wear two or three pieces of kente wrapped around the body with a matching blouse, and men usually wrap one large piece around their body and left shoulder, leaving the right shoulder and arm uncovered.

With the onset of modern living and social changes in Africa, there have been significant changes in how kente cloth is used. According to Ashanti tradition, the size and design of one’s cloth varies according to gender, age, marital status, and social standing. However, in contemporary society, these guidelines are often ignored and kente attire is regularly chosen according to personal preference. Still, color and pattern symbolism linger as part of modern kente cloth apparel: patterns with a predominately yellow design symbolize royalty, wealth, and fertility; pink represents femininity, calmness, and sweetness; green indicates growth, fruitfulness, and spiritual rejuvenation; red, the color of blood, is associated with heightened spiritual and political mood, sacrifice and struggle; blue signifies spirituality and peace; and purple and maroon represent the healing power of the Earth. The most important color, which is used in most kente patterns and is representative of maturity, energy, antiquity, and spiritual potency, is black.

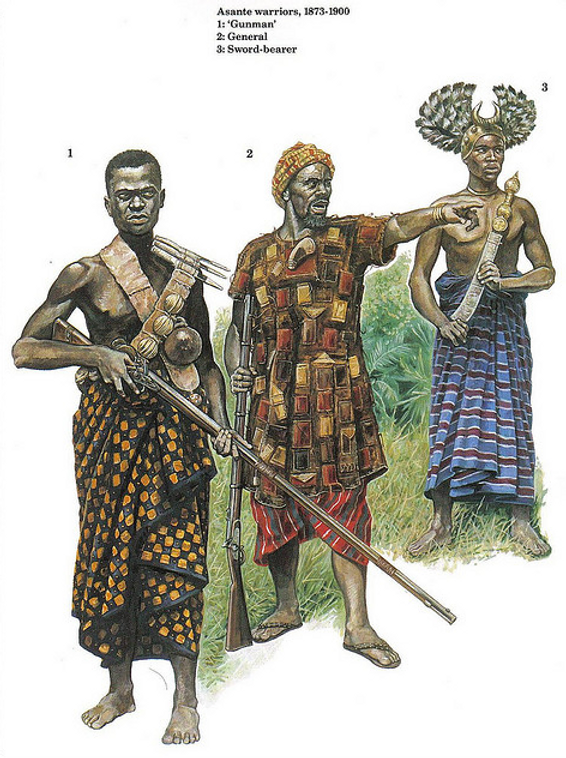

Although the Ashanti maintained traditional beliefs, Muslim traders and Christian missionaries won some converts among them to their respective religions. During the 19th century, the Ashanti fought several wars with the British, who sought to eliminate the slave trade and expand their control in the region. A series of defeats at the hands of the British gradually weakened and reduced the territory of the Ashanti kingdom. After nearly a century of resistance to British power, the Ashanti kingdom was finally declared a Crown Colony in 1902 following the uprising known as the Yaa Asantewa War.

Before long, however, the Ashanti reemerged to contribute to the nationalist movement that would help shape modern Ghana. The exiled Ashanti king was allowed to return to Kumasi in 1924, and the British recognized the Ashanti Confederacy as a political entity in 1935. Today, most Ashanti live in the Ashanti Region of Ghana. They are primarily farmers, growing cocoa for export and yams, plantains, and other produce for local consumption. The Golden Stool, the Ashanti imperial palace, and artifacts at the Museum of National Culture in Kumasi have become enduring symbols of Ghana’s illustrious past.

Getting There: Visit our African Homecoming page — a page dedicated to African history, Africa’s great civilizations, people, places, history, culture, and traditions and uncover the untold stories of the diverse and vast African continent. Encompassing a wide range of experiences, the page is inspired by our travelers who are cultural ambassadors, erudite for ebullient discussions, gluttons for authentic cultural experiences and stories, with an inveterate passion for travel. We’re always here to take the guesswork out of your travel experiences to the African continent – experiences that shift perspectives and fuel imagination.