Masai People, Kenyan Rift Valley have a rich tradition of oral storytelling as a way of passing indigenous environmental knowledge across generations. Credit: Joan de la Malla

Storytelling is deeply rooted in African cultures across the continent and in every ethnicity, serving a deeper purpose and meaning. Global culture is known for movies, music, poetry and literature, storytelling and folklore on the other hand, are embed in African traditions and cultures and has influenced the way African societies and communities live and preserve their values.

Storytelling is the fabric of the African traditional society and community that seeks to transfer values, knowledge, wisdom, customs and traditions from one generation to another. With the aim that these stories will live on forever to inspire the next generation but most importantly perhaps help them understand preserve and appreciate their roots and the roots of our ancestry.

Living Legend and griot Singer, Youssou N’dour

In African society, storytelling takes many forms. Most commonly are oral traditions, artistic expressions through songs, music, folktales, chants, dance, riddles, proverbs as writing wasn’t known then. Ancient writing does exist in African culture, however, most stories are from oral traditions and artistic expressions rather than literature.

Photo Credit: The Clayton County Library System

What’s more fascinating is how the ancestors made sure that the stories live and gets transferred to generations upon generations without losing their essence and context. I remember as a child, we will gather around in a circle form to listen to elders tell stories, folklore, play riddle games and proverbs about many things, such as life, warriors, ancestors, animals and others. This was definitely one of the fun ways to entertain kids before we retire for the night. These stories and tales are usually told with high aesthetic and ethical standards so as to keep their originality and context.

Children Story Time

In music for example, the professional storytellers and musicians are the Griots (French word), Jali (Mandingo, Mende, Malinke, Maninke, Mandinka, Susu, Bambara, word), Gewel (Wolof word), Gnawa from Morocco, Azmari (singer, in Amharic) from Ethiopia. The root meaning of jali is blood, these are people who inherited a unique talent and skill for storytelling and singing from their ancestors, clan, and is part of their lineage. Many griots play the Kora, a long-necked harp lute with 21 strings. Griots as explained by Paul Oliver, “is required to sing on demand the history of a tribe or family for seven generations and, in particular areas, to be totally familiar with the songs of ritual necessary to summon spirits and gain the sympathy of the ancestors.” And in another explanation by Tierno S. Bah, “The griot blends pre-Islamic and Islamic knowledge systems and values. He cultivates both Muslim scholarship and esoteric tradition.” That’s why in Africa to be a singer signifies with talent and that usually means it’s embed in your blood. For example the Jali’s recount the epic histories of the great Mande warrior and King Sunjatta Keita, the founder of the Mande Empire of Mali. The art of the Jali’s lies in their ability to eloquently use words and praise whoever they are singing about. They have a gift of speak, a great way with words and a powerful vocal talent that is agile, angelic, charismatic, golden, heroic etc., and they are great performers and orators. Few famous griots are Lalo Kebba Drammeh, Jalibah Kuyateh from The Gambia Youssou Ndour, Baba Maal from Senegal, and Salif keita from Mali etc.

In Mauritania, the Moorish society also has a strict hierarchical class system with their musicians – again. As a hereditary caste, their skills are inherited from their ancestors and their parents from father to son, or mother to daughter. In Morocco, Marrakesh’s famous Jemaah-el-Fna square is a great melting pot for a rich variety of storytelling traditions. The halca is the circle of listeners and spectators that forms around the halaiqui (storyteller) as he tells tales. If you have heard of classical works such as The Thousand and One Nights and Antaria, legends based on Xeha, Aicha and Kandixa are few popular folk heroes. In South Africa, on the other hand, according to Tim Sheppard, “Praise poems (isibongo) are composed by praise poets (iimbongi, singular imbongi, in Nguni (Xhosa, Zulu and Swati)) whenever an occasion arises or whenever there is something to recite an isibongo about. An imbongi can compose a praise poem about virtually anything. For example, there may be praise poems about people, animals, natural phenomena, important events (good or bad), life and death. One may find isibongo of censure, elegiac ones, besides ones of real praise. Isibongo are composed on the spur of the moment. An imbongi wears a special dress, usually animal skins, and a hat called isidlokolo in Xhosa. A praise poet may be a special imbongi for a chief or king. The only qualification that one needs is expertise in praise singing.” In Tanzania, there are legendry tales of cultural heroes and important ancestors who were intelligent, courageous and generous According to the Bahaya people, a young groom will research the history of his family then he will choose an ancestor who he will try to emulate and use as his role model. “In a very real sense, these ancestors participate and influence the lives of people today,” according to the Tanzania Folklore, from the East African Living Encyclopedia. In Uganda Part of Uganda was once a powerful royal kingdom called Buganda. As always with court life there was plenty of storytelling and praise singing. In Kenya, “the Swahili people on Kenya’s coast have had a rich oral tradition that has been influenced by Islam. Stories of genies are told side by side with stories of hare and hyena. There is also a very rich tradition of popular poetry that has been part of Swahili cultural life for over four centuries,” according to Kenya Folklore – East Africa Living Encyclopedia.

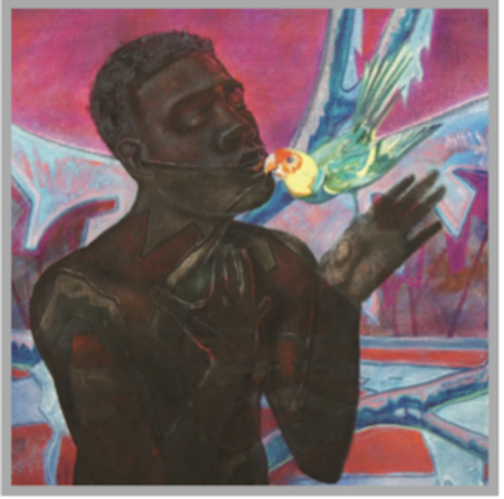

Sometimes storytelling in artistic expressions like dance and rituals and performances for example have spiritual significances or be a form of spiritual transcendence. According to Prof. Misty Bastian & students, “the Mande people are very magical in nature. This can be mostly attributed to the nyamakalaw subgroup; an endogamous people who are born with the inherent ability to control nature. The power they are able to wield so well is called nyama. In fact, their name nyama-kala could be translated as handlers (kala) of nyama. The Mande see nyama as a hot, wild energy that is the animating force of nature. Nyama is present in all the rocks, trees, people and animals that inhabit the Earth. It is similar to the Western notion of the soul but is more complete than that. It controls nature, the stars and the motions of the sea. Nyama is truly the sculptor of the universe.” A popular performance and artistic expression the Mandinka’s in The Gambia has is the performance by a Kanguran and Ifanbondi. Kankuran is played by a man who takes on the role of an age-old spirit and guardian. He usually comes out during periods of male circumcision to cleanse and chase away evil spirits. He is a frightening and terrifying figure dressed in leaves and bark and red fibers from an oak-like tree called the Faare and carries a cutlass or machete and usually have a Jobo (guide, intermediary) between themselves and the people. The Jobo speaks for the Kankuran. Ifanbondi on the other hand is more frightening and terrifying than Kankuran, commissioned to restrict and threaten the evil advocates during male circumcision. The safety of the newly circumcised is not left to the agency of God alone, but regulated by the inter-mediators of our humanly world, the Ifanbondis. Ifanbondi literally means in Mandinka someone who change into another form and are individuals who are said to be in Mandinka, (Kun Fanunteh) someone with seven sense or extra ordinary visions. Ifanbondis plays a part in helping restore calmness in situations to fight the all-powerful, night travelers (Witch’s), they are the antidotes of Witches. They can fight them spirit to spirits. Almost everyone in the village will not dare come out when Ifanbondi takes its form. There are significant differences between Kankuran and Ifanbondi. Whilst Kankurans discipline youths, and even adults, they cannot enter into the realms of the deep spirits. Also the Kankuran are social entertainers, whilst the Ifanbondis are not. The Kankuran can sing and dance, the Ifanbondi cannot even be identified let alone entertain the people and have spiritual knowledge. As the sayings goes, familiarity breeds contempt, no one knows who takes form of Ifanbondi, that logic is utilized by the elders in sensitively disguising or keeping the identity of the Ifanbondi a top secret. The Ifanbondi is usually someone from a different neighbourhood, but it can also be a native. The intention of both the Kankuran and Ifanbondi is rooted in abstruse mysteries and self-mortification.

I heard this particular story from Elizabeth Gilbert in her TED Talk about “Your Elusive Creative Genius,” in which she perfectly illustrated a tradition in Northern Africa for example, centuries ago, people used to gather around for moonlight dances of sacred nature along with music that would go on for hours until dawn. The dancers were always magnificent and terrific. And once in a while, very rarely, something magical would happen, and one of these performers would almost become transcendent.

As Gilbert descried, “it was like time would stop, and the dancer would sort of step through some kind of portal and he wasn’t doing anything different than he had ever done, 1,000 nights before, but everything would align. And all of a sudden, he would no longer appear to be merely human. He would be lit from within, and lit from below and all lit up on fire with divinity.” When this rare thing happened people knew it for what it was, to their amazement, they would put their hands together and start chanting, “Allah, Allah, Allah, God, God, God.” Gilbert went on to add how the “Olé, Olé, chant that we frequently hear in soccer/football games and other sports originated. According to Gilbert, “when the Moors invaded southern Spain, they took this custom with them and the pronunciation changed over the centuries from “Allah, Allah, Allah,” to “Olé, Olé, Olé, which you still hear in bullfights and in flamenco dances. In Spain, when a performer has done something impossible and magic, “Allah, olé, olé, Allah, magnificent, bravo,” incomprehensible, there it is — a glimpse of God.”

In Kenya and Madagascar, storytelling is currently being used as a tool to revitalise the biocultural heritage of indigenous peoples. According to an article by the University of Helsinki, titled, “Indigenous storytelling is a new asset for biocultural conservation,” most of the world’s biodiversity are those inhabited by indigenous peoples. The purpose of this according to Fernández-Llamazares, “while listening to stories, conservation practitioners may become more aware of indigenous worldviews, so the act of storytelling may facilitate dialogue. By promoting such encounters, the tradition of storytelling is then revitalized, helping to maintain intergenerational exchanges and the transmission of local environmental knowledge.” In Madagascar, storytelling projects in conservation contexts have included a local radio programming to encourage lemur conservation in Madagascar, and a mobile storybooth documenting community efforts to conserve nature in a project assisting indigenous youth to document traditional wildlife stories from their elders in North Kenya.